Embracing the Cumbersome Locality. Notes on Petr Štembera’s Relevance Today

/5

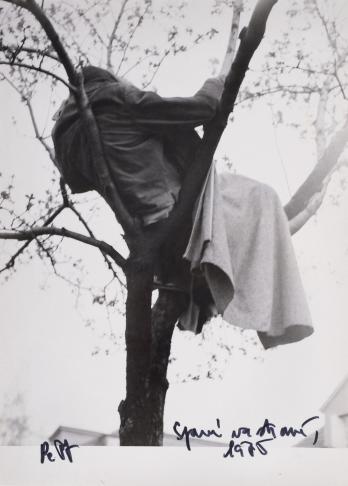

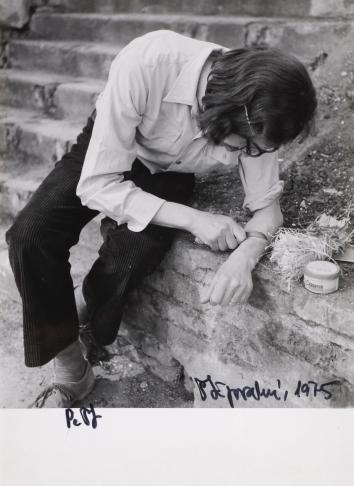

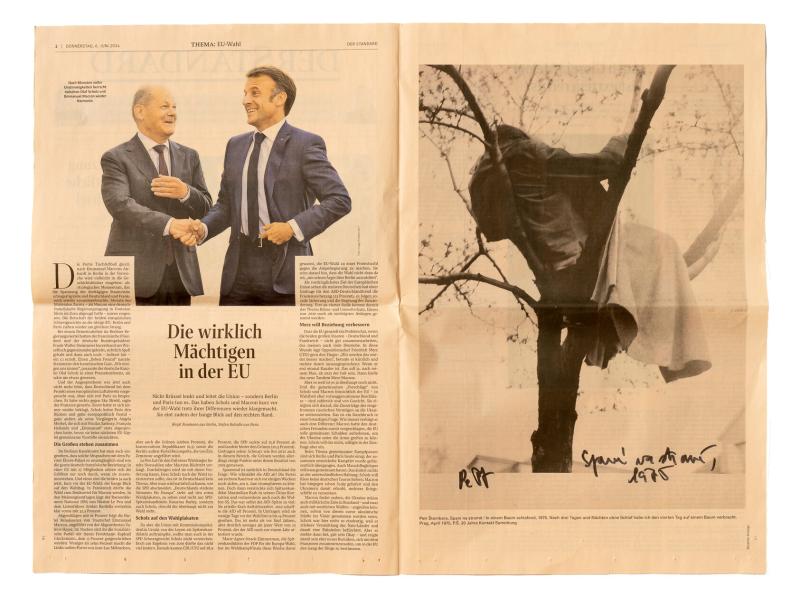

On the occasion of the Kontakt Collection’s twentieth anniversary, a documentary photograph of Petr Štembera’s performance “Sleeping in a Tree” (1975) was reproduced as a full-page image in the Austrian daily “Der Standard,” where it appeared in close proximity to a snapshot of a meeting between French president Emmanuel Macron and German chancellor Olaf Scholz.¹ This renewed attention to Štembera’s oeuvre is nothing unusual; it would seem that his work resonates in the context of contemporary art. “Grafting” (1975), in which he used “a common method in fruit-farming” to graft a branch onto his arm, was exhibited at this year’s Biennale Matter of Art in Prague along with four other performance photographs. Curators Aleksei Borisionok and Katalin Erdődi even adopted the metaphor of making connections so as to optimize resilience when they discussed their efforts to connect heterogenous geographies, narratives, and terminologies: “We ask ourselves how we can extend branches of solidarity and bridge the gap between the countryside and the city, bringing them from the factories to the fields. How can we establish new alliances and grow and gain strength together instead of allowing our differences to divide us?”²

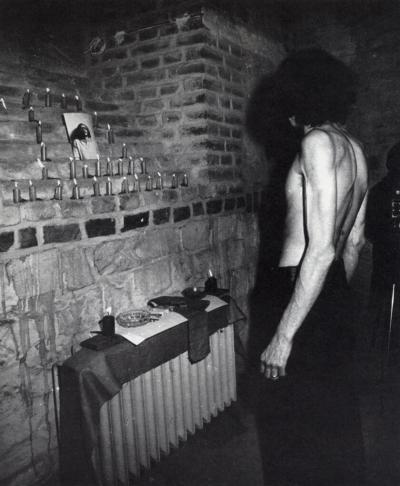

The supra-regional and timeless comprehensibility of Štembera’s mid-1970s performances, which saw him challenge the physical limits of his body or attempt to merge with nature,³ was underlined by his choice of materials and motifs similar to those being worked with by other artists at the time. Just like Gina Pane, for example, Štembera also moved stones [“Transposition of Two Stones” (1971)]; when we consider “Grafting” and other self-destructive activities, we are reminded of Chris Burden and his “danger pieces”; an interest in burning [“Extinguishment” (1975)] connects Štembera to Terry Fox; and bodily fluids, nails, and hair [“Narcissus”(1974-1978)] were also used by Marina Abramović. What’s more, the black-and-white photographs and brief verbal descriptions through which we experience Štembera’s performances were produced in a comprehensible style, regardless of where they were created. Štembera attempted systematically to stay connected with the international scene. Not only did his documentary format correspond to the standards of the period, it also allowed him to bypass the lack of an institutional network or any form of support for this type of art in Czechoslovakia. At a time when it was impossible to perform or exhibit documentary materials in galleries, Štembera would send his photographs to artists, curators, and magazine editors, arranging exhibitions abroad by correspondence. He thus himself became the embodiment of the institution, creating his own support network and succeeding in “infiltrating the artworld”⁴ with his performances.

His later performances, however, are well out of the spotlight—just as much now as when they were created. In these pieces, he became more and more immersed in the local context of the times. They came to a head in an event realized on 20 December 1980 at the studio of Vladimír Ambroz in Brno that ultimately turned out to be the definitive end of Štembera’s activities in the field of art. He confronted the spectators, who were accustomed to “consuming” non-conformist art, with the new hit single by Michal David—then a seventeen-year-old rising star of socialist pop—who first came to prominence in 1980 with “Žít tak, jak se má” [Living As One Should]. In his typewritten commentary on this performance, Štembera emphasized his view that the song was one of the most “striking examples” of how the communist regime had finally adopted the American strategy of appropriating a particular cultural phenomenon—in this case, rock music—with the aim of promoting pragmatic ideals: “growing only as far as our skin lets us.”⁵ Štembera turned this logic inside-out and appropriated normalization-era pop culture in his piece: wearing a suit, he stood on his head and sang along to the recording: “living as one should, that’s the only way I’d want to live.” It is symptomatic that, not much later, František Janeček—the driving force behind normalization-era pop music (his orchestra also accompanied Michal David)—lent out his sound system for the 1989 protests.⁶ Janeček always knew which way the wind was blowing. And in 2018, on the occasion of the celebration of the centenary of the founding of Czechoslovakia, Michal David received a state decoration from president Miloš Zeman. As he sings in one of his greatest hits, “Poupata” [Flower Buds], written for the 1985 Spartakiad, a mass gymnastics event organized by the Communist government every five years: “A beautiful lot we have today / To walk towards tomorrow, live and bloom… / When what should go well goes well / It is yet a beautiful world.” This is why these virtually unknown later works by Štembera can indeed be highly relevant to us today, particularly in a part of the world whose development is taking place in close relation to the issues faced by the Euro-Atlantic region and its contemporary populist politics.

If Štembera was testing the borders of his own resilience in his earlier, now well-known performances, these pieces saw him also compel his audience to go outside of their comfort zone. He thus abandoned the safe space he had himself created, one separated from socialist culture, in order to then subject it to contemporary reality by reading newspapers, watching television, and listening to radio broadcasts as well as normalization-era pop music. This shift, which soon led him to view producing any further art as an impossibility, also complicates the reading of Štembera’s oeuvre, whether from the perspective of Western art history of the time or from today’s perspective. Perhaps he is simply alerting us to the fact that despite efforts to understand the variability of the former Eastern Bloc, we still have a tendency—even as we try to avoid exoticization—to prefer timeless and supra-regional comprehensibility to the heavy-footed, exotic, socialist locality. According to Štembera, only by abandoning not just that which leads nowhere but also—and especially—that which works can we ensure that we do not become alienated from ourselves: “I’m still after instability, and I’d be undermining myself if I were to define that which is not defined,” he stated in an interview.⁷ Several years ago, Tomáš Pospiszyl challenged art historians in our region to stop situating Eastern European neo-avant-garde art in the context of the Western art world.* Štembera’s late performances, in their “grafting” of official pop and art presented to a handful of friends, would seem to connect these worlds in an almost unpleasantly literal manner.

Hana Buddeus

Translated from Czech by Ian Mikyska

Hana Buddeus is an art historian based in Prague. She is a member of the Photography Research Centre (CVF) and a researcher at the Institute of Art History of the Czech Academy of Sciences. Buddeus is interested in the intersections of photography studies and art history, especially as this pertains to reproductions of works of art. As a curator, she has prepared several editions of the Fotograf Festival and participated in editing the associated magazine “Fotograf.”

1

Der Standard, June 6, 2024, pp. 2–5.

2

Cf. Interview with Katalin Erdődi and Aleksei Borisionok led by Anna Remešová for Artalk. Available at: https://artalk.info/news/katalin-erdodi-a-aleksei-borisionok-nasi-kuratorskou-metodou-je-roubovani and Sowing Unrest, a reader published on the occasion of the Biennale Matter of Art, Aleksei Borisionok & Katalin Erdődi (eds.), Prague: tranzit.cz & Spector Books 2024, p. 18.

3

Karel Srp, Karel Miler, Petr Štembera, Jan Mlčoch. 1970–1980, exh. cat., Prague: Prague City Gallery 1998, p. 6.

4

My publications on the topic include “Photography: The Lingua Franca of Performance Art,” “ArtMargins Online,” available at: https://artmargins.com/photography-the-lingua-franca-of-performance-art/; “Infiltrating the Art World through Photography. Petr Štembera’s 1970s Networks,” in “Actually Existing Artworlds of Socialism,” ed. Reuben Fowkes, special issue, “Third Text 32,” no. 153 (2018): pp. 468–484; “Zobrazení bez reprodukce? Fotografie a performance v českém umění sedmdesátých let 20. Století” [Representation without Reproduction? Photography and Performance in Czech Art of the 1970s] (Prague: UMPRUM, 2017).

5

Now held at The Archive of the National Gallery Prague: Petr Štembera fonds, reference no. 156.

6

Pavel Klusák, “Jazzman Michal David,” Lidové noviny, September 19, 2009. Available at: https://www.lidovky.cz/domov/jazzman-michal-david.A090919_000100_ln_noviny_sko

7

Undated quotation of Petr Štembera. Cited according to Karel Srp, “Karel Miler, Petr Štembera, Jan Mlčoch. 1970–1980,” exh. Cat., Prague: Prague City Gallery 1998, p. 9.

*

Tomáš Pospiszyl, “Tasks for the study of Eastern European art during the socialist era,” 2018. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/42699490/Tasks_for_the_Study_of_Eastern_European_Art_During_the_Socialist_Era.

November 2024

The supra-regional and timeless comprehensibility of Štembera’s mid-1970s performances, which saw him challenge the physical limits of his body or attempt to merge with nature,³ was underlined by his choice of materials and motifs similar to those being worked with by other artists at the time. Just like Gina Pane, for example, Štembera also moved stones [“Transposition of Two Stones” (1971)]; when we consider “Grafting” and other self-destructive activities, we are reminded of Chris Burden and his “danger pieces”; an interest in burning [“Extinguishment” (1975)] connects Štembera to Terry Fox; and bodily fluids, nails, and hair [“Narcissus”(1974-1978)] were also used by Marina Abramović. What’s more, the black-and-white photographs and brief verbal descriptions through which we experience Štembera’s performances were produced in a comprehensible style, regardless of where they were created. Štembera attempted systematically to stay connected with the international scene. Not only did his documentary format correspond to the standards of the period, it also allowed him to bypass the lack of an institutional network or any form of support for this type of art in Czechoslovakia. At a time when it was impossible to perform or exhibit documentary materials in galleries, Štembera would send his photographs to artists, curators, and magazine editors, arranging exhibitions abroad by correspondence. He thus himself became the embodiment of the institution, creating his own support network and succeeding in “infiltrating the artworld”⁴ with his performances.

His later performances, however, are well out of the spotlight—just as much now as when they were created. In these pieces, he became more and more immersed in the local context of the times. They came to a head in an event realized on 20 December 1980 at the studio of Vladimír Ambroz in Brno that ultimately turned out to be the definitive end of Štembera’s activities in the field of art. He confronted the spectators, who were accustomed to “consuming” non-conformist art, with the new hit single by Michal David—then a seventeen-year-old rising star of socialist pop—who first came to prominence in 1980 with “Žít tak, jak se má” [Living As One Should]. In his typewritten commentary on this performance, Štembera emphasized his view that the song was one of the most “striking examples” of how the communist regime had finally adopted the American strategy of appropriating a particular cultural phenomenon—in this case, rock music—with the aim of promoting pragmatic ideals: “growing only as far as our skin lets us.”⁵ Štembera turned this logic inside-out and appropriated normalization-era pop culture in his piece: wearing a suit, he stood on his head and sang along to the recording: “living as one should, that’s the only way I’d want to live.” It is symptomatic that, not much later, František Janeček—the driving force behind normalization-era pop music (his orchestra also accompanied Michal David)—lent out his sound system for the 1989 protests.⁶ Janeček always knew which way the wind was blowing. And in 2018, on the occasion of the celebration of the centenary of the founding of Czechoslovakia, Michal David received a state decoration from president Miloš Zeman. As he sings in one of his greatest hits, “Poupata” [Flower Buds], written for the 1985 Spartakiad, a mass gymnastics event organized by the Communist government every five years: “A beautiful lot we have today / To walk towards tomorrow, live and bloom… / When what should go well goes well / It is yet a beautiful world.” This is why these virtually unknown later works by Štembera can indeed be highly relevant to us today, particularly in a part of the world whose development is taking place in close relation to the issues faced by the Euro-Atlantic region and its contemporary populist politics.

If Štembera was testing the borders of his own resilience in his earlier, now well-known performances, these pieces saw him also compel his audience to go outside of their comfort zone. He thus abandoned the safe space he had himself created, one separated from socialist culture, in order to then subject it to contemporary reality by reading newspapers, watching television, and listening to radio broadcasts as well as normalization-era pop music. This shift, which soon led him to view producing any further art as an impossibility, also complicates the reading of Štembera’s oeuvre, whether from the perspective of Western art history of the time or from today’s perspective. Perhaps he is simply alerting us to the fact that despite efforts to understand the variability of the former Eastern Bloc, we still have a tendency—even as we try to avoid exoticization—to prefer timeless and supra-regional comprehensibility to the heavy-footed, exotic, socialist locality. According to Štembera, only by abandoning not just that which leads nowhere but also—and especially—that which works can we ensure that we do not become alienated from ourselves: “I’m still after instability, and I’d be undermining myself if I were to define that which is not defined,” he stated in an interview.⁷ Several years ago, Tomáš Pospiszyl challenged art historians in our region to stop situating Eastern European neo-avant-garde art in the context of the Western art world.* Štembera’s late performances, in their “grafting” of official pop and art presented to a handful of friends, would seem to connect these worlds in an almost unpleasantly literal manner.

Hana Buddeus

Translated from Czech by Ian Mikyska

Hana Buddeus is an art historian based in Prague. She is a member of the Photography Research Centre (CVF) and a researcher at the Institute of Art History of the Czech Academy of Sciences. Buddeus is interested in the intersections of photography studies and art history, especially as this pertains to reproductions of works of art. As a curator, she has prepared several editions of the Fotograf Festival and participated in editing the associated magazine “Fotograf.”

1

Der Standard, June 6, 2024, pp. 2–5.

2

Cf. Interview with Katalin Erdődi and Aleksei Borisionok led by Anna Remešová for Artalk. Available at: https://artalk.info/news/katalin-erdodi-a-aleksei-borisionok-nasi-kuratorskou-metodou-je-roubovani and Sowing Unrest, a reader published on the occasion of the Biennale Matter of Art, Aleksei Borisionok & Katalin Erdődi (eds.), Prague: tranzit.cz & Spector Books 2024, p. 18.

3

Karel Srp, Karel Miler, Petr Štembera, Jan Mlčoch. 1970–1980, exh. cat., Prague: Prague City Gallery 1998, p. 6.

4

My publications on the topic include “Photography: The Lingua Franca of Performance Art,” “ArtMargins Online,” available at: https://artmargins.com/photography-the-lingua-franca-of-performance-art/; “Infiltrating the Art World through Photography. Petr Štembera’s 1970s Networks,” in “Actually Existing Artworlds of Socialism,” ed. Reuben Fowkes, special issue, “Third Text 32,” no. 153 (2018): pp. 468–484; “Zobrazení bez reprodukce? Fotografie a performance v českém umění sedmdesátých let 20. Století” [Representation without Reproduction? Photography and Performance in Czech Art of the 1970s] (Prague: UMPRUM, 2017).

5

Now held at The Archive of the National Gallery Prague: Petr Štembera fonds, reference no. 156.

6

Pavel Klusák, “Jazzman Michal David,” Lidové noviny, September 19, 2009. Available at: https://www.lidovky.cz/domov/jazzman-michal-david.A090919_000100_ln_noviny_sko

7

Undated quotation of Petr Štembera. Cited according to Karel Srp, “Karel Miler, Petr Štembera, Jan Mlčoch. 1970–1980,” exh. Cat., Prague: Prague City Gallery 1998, p. 9.

*

Tomáš Pospiszyl, “Tasks for the study of Eastern European art during the socialist era,” 2018. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/42699490/Tasks_for_the_Study_of_Eastern_European_Art_During_the_Socialist_Era.

November 2024