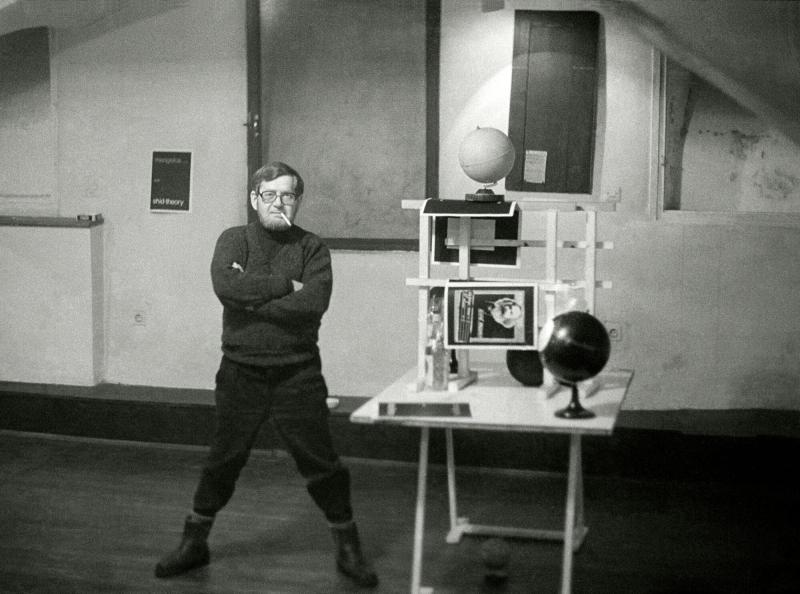

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos

Dimitrije Bašičević was an art historian, critic and curator at various Zagreb galleries. At the same time, though less famously, he was also an artist who worked under the pseudonym Mangelos (after a village near his birthplace of Šid). His oeuvre, according to later periodizations by Mangelos, starts in the postwar period with a number of work groups: “Paysages de la mort,” “Paysages de la guerre,” “Paysages,” and “Tabula Rasa” (black and white monochrome surfaces with text written underneath), which he used to express a state of oblivion and the setting for a new beginning. Taking up positions

embodied by the “anti-art” of the Gorgona Group, Mangelos denied painting in the series “Pythagoras, Anti-peinture” and “Abecede”—accentuating the rational as the compositional factor in art. He later wrote ideas, poetry (No-stories) and manifestos in black, red and white color, in calligraphy between drawn lines, in a hybrid form of writing and painting in notebooks, on wooden boards and on globes. During the ’seventies, Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos the curator followed conceptual and media art, especially photography, but Mangelos the artist was inclined more toward defining terms and conceptualizing ideas. Simultaneously supported by a younger generation of artists, he tended to show his work in alternative, artist-run exhibition spaces. Just as before, Mangelos was in dialog—or rather in dispute—with everything he was studying, and his spectrum was broad, running from philosophy and art to psychoanalysis, to biology… Texts represented a specific form in which to express highly subjective stances dominated by the theory of the “machine civilization” and “functional thought,” with which he affirmed his ideas about society’s development and art’s non-development, i.e. about the crisis and death of art, explaining this in light of the rift between two civilizations: the “handmade” and the “machine,” the former being based on “old, naïve and metaphoric” and the latter on “functional” thought. Humor and irony were always present—in exhibiting ideas, in the discrepancy between a pretentious message and a banal sentence, in scorning authority, and in mixing various foreign languages (particularly German, French and English). Aware that such writing did not reflect the precision of the functional thought they were advocating, his manifestos became increasingly succinct (especially those written on globes). He wished to reduce information to the shortest possible form, to a clear and precise thought—a “super-Wittgenstein” thought, as he himself put it. Chronologically, Mangelos’s work coincided with the feeling of the absurd in existentialist nihilism, the independent intellectual spirit of Gorgona, the overstepping of medium-entailed framework as practiced by Fluxus, and conceptualism in the use of language and philosophic deliberation. But taken as a whole, his oeuvre was quite authentic and created a specific realm of freedom that Mangelos conquered for himself and called NO-ART. B.S.

more