Alina Lamakh (1925–2020)Persistence through Art

/2

I remember the first time I saw her—briefly, in Kiev during 1970s. She and her husband Valery Lamakh had dropped in to greet their friend Anja Zavarova, an art historian living on left bank of the Dnieper river. Anja was hosting a bunch of students—visitors from Czechoslovakia. Alina was all in white, and Valery wore a beret on his head. Both of them were smiling and appeared as if they perhaps felt a bit alienated by the bunch of young people they found there, sitting on the floor and drinking Soviet champagne that sunny afternoon.

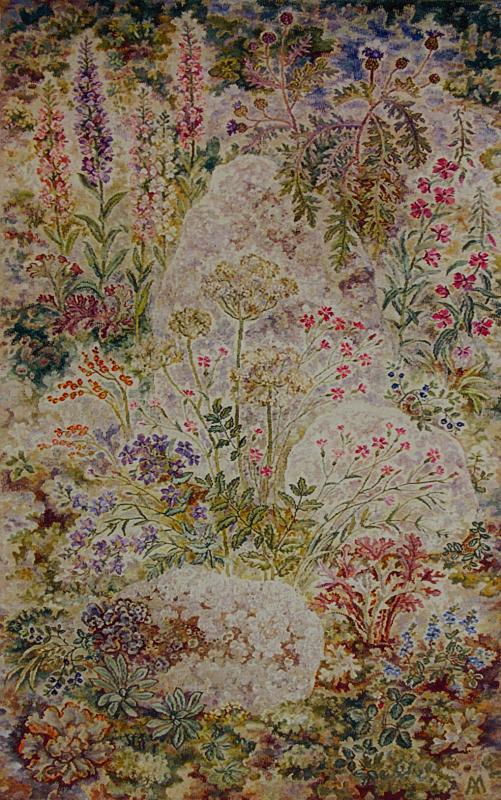

Later on, we saw her only rarely. I heard she was busy, at work every day in the studio that she shared with Valery. It was there that she had her loom and continued to meticulously weave her complicated tapestries, featuring mostly plants and flowers. She spent long hours looking at the patterns, her fingers elegantly assembling and disassembling threads.

Nearly forty years passed before we met again. In 2015, I visited her in Kiev to find out more about the talk that, back in 1970s, Valery Lamakh had been in the habit of smuggling his geometric schemes, meant as messages to be deciphered in the future, into his large-scale art works (Soviet state propaganda images on the facades of public buildings, mostly mosaics). “Yes,” she said, “they are part of the composition on the façade of Khlopchato-bumazhnyi Kombinat (a textile factory) in Ternopil; and the Soviet censors charged with ensuring artworks’ ideological impeccability suspected nothing, taking it for non-committal ornamentation”. Sitting in front of her, I could see how beautiful her hands were. “I liked difficult puzzles, and sometimes, weaving even just a single centimetre could take days and days”, she says.

Lamakh still had all of her grace—whether in the movement of her hands or in her deliberate, concentrated way of speaking about Valery’s works, his large series of gouache drawings: over a period of 33 years, he drew schemata on small plates, depicting transformations of processes of history, culture, and the human beings in them, running in the circles of geometrical signs. On the backs of these plates, which display something like a systematic Weltanschauung, he would write his explanatory notes and deliberations. A circle of friends in Kiev followed his progress with these works—and Alina, the only one who could read his undecipherable handwriting following his death, collected all of his texts, rewriting the backside notes and publishing the completed works in the two-volume publication Books of Schemata.

---

More from our talk:

She said that her mother did not let her go to school until she was nine. She began her first year together with her younger brother, going every day to the nearest village school. Back in the early 1930s, during the famine organized in Ukraine by the Bolsheviks, that was dangerous, as there were cases in which very little girls might be hunted … I didn’t ask for details, and she just looked longer into my eyes.

Hunger was terrible, she said: “My mother and the other women who worked at the food dispatching unit sometimes had to scrape out the remainders of various foodstuffs—rice, salt, sugar, flour—from canvas bags. They would spread out bedsheets on the floor and shake these bags until they’d gathered a handful of edible material. Once, my mother got a small lump of sweet molasses; I couldn’t resist and ate it in secret. She scolded me severely for that.

I met Valery twice: the first time, he readily offered me his hand and heart—and I refused him, since I already had a boyfriend of sorts. He then disappeared. Quite some time later, we met again in Moscow at the railway station, standing in a queue for tickets to Kiev. We ended up travelling together, and we’ve never parted since.

Anna Daučíková, notes written following Alina Nikolaevna’s death at age 94 in Kiev.

Anna Daučíková is an artist. She lives and works in Prague.

May 2020

Later on, we saw her only rarely. I heard she was busy, at work every day in the studio that she shared with Valery. It was there that she had her loom and continued to meticulously weave her complicated tapestries, featuring mostly plants and flowers. She spent long hours looking at the patterns, her fingers elegantly assembling and disassembling threads.

Nearly forty years passed before we met again. In 2015, I visited her in Kiev to find out more about the talk that, back in 1970s, Valery Lamakh had been in the habit of smuggling his geometric schemes, meant as messages to be deciphered in the future, into his large-scale art works (Soviet state propaganda images on the facades of public buildings, mostly mosaics). “Yes,” she said, “they are part of the composition on the façade of Khlopchato-bumazhnyi Kombinat (a textile factory) in Ternopil; and the Soviet censors charged with ensuring artworks’ ideological impeccability suspected nothing, taking it for non-committal ornamentation”. Sitting in front of her, I could see how beautiful her hands were. “I liked difficult puzzles, and sometimes, weaving even just a single centimetre could take days and days”, she says.

Lamakh still had all of her grace—whether in the movement of her hands or in her deliberate, concentrated way of speaking about Valery’s works, his large series of gouache drawings: over a period of 33 years, he drew schemata on small plates, depicting transformations of processes of history, culture, and the human beings in them, running in the circles of geometrical signs. On the backs of these plates, which display something like a systematic Weltanschauung, he would write his explanatory notes and deliberations. A circle of friends in Kiev followed his progress with these works—and Alina, the only one who could read his undecipherable handwriting following his death, collected all of his texts, rewriting the backside notes and publishing the completed works in the two-volume publication Books of Schemata.

---

More from our talk:

She said that her mother did not let her go to school until she was nine. She began her first year together with her younger brother, going every day to the nearest village school. Back in the early 1930s, during the famine organized in Ukraine by the Bolsheviks, that was dangerous, as there were cases in which very little girls might be hunted … I didn’t ask for details, and she just looked longer into my eyes.

Hunger was terrible, she said: “My mother and the other women who worked at the food dispatching unit sometimes had to scrape out the remainders of various foodstuffs—rice, salt, sugar, flour—from canvas bags. They would spread out bedsheets on the floor and shake these bags until they’d gathered a handful of edible material. Once, my mother got a small lump of sweet molasses; I couldn’t resist and ate it in secret. She scolded me severely for that.

I met Valery twice: the first time, he readily offered me his hand and heart—and I refused him, since I already had a boyfriend of sorts. He then disappeared. Quite some time later, we met again in Moscow at the railway station, standing in a queue for tickets to Kiev. We ended up travelling together, and we’ve never parted since.

Anna Daučíková, notes written following Alina Nikolaevna’s death at age 94 in Kiev.

Anna Daučíková is an artist. She lives and works in Prague.

May 2020