Ivan Kožarić (1921–2020)A Century-Long Journey on the Trail of Art

/8

“I am not an artist, but I compensate by being a poor sculptor. In my research, I have come to a position where I can say I am on the trail of art, and this is enough for me.”

Ivan Kožarić

“Our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction.”

Francis Picabia

“Death is the negation of an alive life, death is a new life, therefore let us cry wholeheartedly as we rejoice to the fullest in the abundance of life.”

Ivan Kožarić

News of the passing of Ivan Kožarić (1921–2020), an artist who not only lived a whole century but also “sculptured” it through his work, left me with the impression that his cycles of works have continually rearranged in a process of playful transformations and have not simply been concluded by his departure. This is partially due to his understating of time. His rejection of a chronological or evolutionary principle in terms of his work was something that he shared with his fellow colleagues Julije Knifer and Dimitrije Bašičević (Mangelos) of the avant-garde group Gorgona.(1) Kožarić often left his works without a signature or a date; one work spontaneously grew from another; works were arranged into cycles, and later into different ones in a never-ending process of permutation. His exploration of possibilities of the anti-sculptural and gestures of collectivity often went against and beyond the physical barriers of a single object and setting. What’s more, there were no boundaries between sculpture and the rest of the world. Sculpture as a medium was tested via the usage of conceptual proclamations, utopian concepts, textual works, drawings, paintings, performatives, encountered situations, urban interventions ...

The works created by Kožarić, whether object-based or of a conceptual nature, function as portals that look behind the existing into another dimension. This process is exemplified by his iconic sculpture “Unutarnje oči” (“Inner Eyes”, 1959—60), which expands into a negative, empty space. It consists of an enigmatic semicircular hollow object (of which he created several versions in different materials) that depicts the interior of a head (we assume the artist’s own) in which the two protruding forms signify the inward trajectory of a gaze. “Inner Eyes” is at once a self-portrait, a manifesto, and a portal. It traces a process in which the artistic gaze looks inward to penetrate the artist’s own head. Through these prosthetic inner eyes, his personal point of view is exposed to the viewers, from whose own point of view the inner eyes appear to stare back from the depths. Kožarić choose the photo of “Inner Eyes” for the cover of his edition of the “Gorgona” anti-magazine (no. 5) in 1961. This choice may have been a nod to the group’s having named itself “Gorgona” after the mythical creature whose divine visage petrified those who beheld it (also a kind of a “sculpturing” event). This choice reflects the Gorgonian collective search for more autonomous ways of producing and discussing art, which they held to be achievable only through a radical shift of perspective.

“Neobični projekt – Rezanje Sljemena” (“Uncommon Project – Cutting Sljeme”, 1960) takes sculpturing to another scale and dimension. Here, Kožarić proposed cutting into part of the Sljeme—a mountain peak popular among Zagreb-based hikers—and turning the landscape into sculptural material. Performative gestures and language were the medium that Gorgona group used for their projects. Kožarić’s “Kolektivno djelo” (“Collective Work”, 1963) proposes making plaster casts of the interiors of all the Gorgona members’ skulls—as well as of cars, of studios, and “mainly, then, of all the significant cavities in our city”. This work was initiated by an exercise suggested by another group member, art historian Radoslav Putar, who asked all members to propose their ideas for the group’s collective work. Kožarić’s proposal that resulted in “Collective Work” was the most remarkable, as a way of brilliantly expanding upon the idea of negative interior space originally worked with in his “Inner Eyes”.

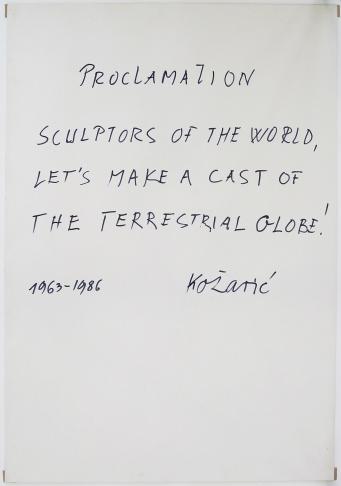

Gorgona’s synergistic collective ethos, its transgressive ideas on the dissolution of art, catalyzed many of Kožarić’s projects that engaged with conceptualizing realms of negative and utopian sculptural space, which he viewed as being supplementary to external, concrete spaces. A text-based piece entitled “Proglas” (“Proclamation”, 1963–86)—which, in a spirit of collectivity, extends the invitation: “Sculptors of the world, let us make a cast of the Earth’s globe”—in many respects challenges our imaginations to conceive of their utopian potential as being feasible even as we postpone its realization until the future.

Regardless of these expansive energies, the quintessential space of Kožarić’s practice was a microcosm of his own studio, which was originally situated at 12 Medulićeva Street in Zagreb. It was a space that functioned as a junction, a point where all things come together to be invoked.

Being conceived of as an artistic “laboratory of revitalization”(2), his studio underwent numerous transformations. In 1971, he repainted almost everything in it—from sculptures from various periods to everyday objects—in a golden color, thereby equalizing his sculptural masterpieces with the non-art objects. Following this repainting in gold, 1993 saw the entire studio moved to the Zvonimir Gallery in Zagreb for his solo show, for the duration of which he also resided and worked there.(3) After that, the studio was presented in Kassel as part of 2002’s Documenta 11(4), an occasion for which its innate chaos was (ostensibly) structured. And finally, when Studio Kožarić entered the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, another (unexpected) transformation occurred: once all of the sculptures had been restored and wrapped neatly in acid-free paper, ready to be transported to the museum, Kožarić ecstatically decided to exhibit the sculptures while still wrapped—thereby rendering them “invisible”. It was one year later that the sculptures were finally unwrapped for all to see.

***

Another Gorgon, Dimitrije Bašičević (known from 1959 as Mangelos), based his “shid-manifesto” (1977) on “bio-psychological theory”, according to which the cells in a human body are exchanged in their entirety every seven years—meaning that at the conclusion of any such period, one is an entirely “new” person. Mangelos hence made note of “two Rimbauds, two Karl Marxes, three Van Goghs, several Picassos and nine-and-a-half Mangeloses”(5). To paraphrase him in an attempt to guess just how many Kožarićs exist, “a one and incommensurable” would seem a viable answer.

Kožarić’s oeuvre also exhibits a strong sense of humor—for in its use of unexpected and often surreal juxtapositions and dislocations, it also enables shifts in perspective on the part of the spectator. And at the present moment, with the horizon of old paradigms vanishing, we can view Kožarić’s oeuvre as an invitation to partake in the creation of future collective imaginaries. Employing the perspective of Kožarić’s art, this can be established by way of intuitive playfulness as well as via fearless de-hierarchization whose sphere of application includes the personal level. This is what makes his art so alive and so truly groundbreaking.

Ana Dević

(1) In addition to Kožarić, Gorgona included the painters Josip Vaništa, Marijan Jevšovar, Julije Knifer, and Đuro Seder; the architect Miljenko Horvat; the art historians Radoslav Putar, Matko Meštrović; and the art historian, curator and artist Dimitrije Bašicević (Mangelos). The group was active in Zagreb from 1959 to 1966.

(2) See Evelina Turković, “My Studio is a Laboratory for Vivification,” in “The Kožarić Studio”, Meta, Zagreb, 2002, p.80.

(3) This exhibition was initiated and curated by Antun Maračić.

(4) Kožarić was invited by Okwui Enwezor, artistic director of Documenta 11.

(5) See Branka Stipančić, “Mangelos from 1 to 9 ½, No-art”, Museu de Arte Contemporanea de Serrvales, Porto, 2003, p. 13.

The author would like to thank Radmila Iva Janković, curator of the Studio Kožarić at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb for collegially sharing her knowledge; Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, Boris Cvjetanović, Tomislav Pernar and his family, Dorotea Jendrić, Mio Vesović, and Goran Vranić.

Ana Dević is a curator and educator living in Zagreb. She is a member of curatorial collective What, How and for Whom/WHW.

November 2020

Ivan Kožarić

“Our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction.”

Francis Picabia

“Death is the negation of an alive life, death is a new life, therefore let us cry wholeheartedly as we rejoice to the fullest in the abundance of life.”

Ivan Kožarić

News of the passing of Ivan Kožarić (1921–2020), an artist who not only lived a whole century but also “sculptured” it through his work, left me with the impression that his cycles of works have continually rearranged in a process of playful transformations and have not simply been concluded by his departure. This is partially due to his understating of time. His rejection of a chronological or evolutionary principle in terms of his work was something that he shared with his fellow colleagues Julije Knifer and Dimitrije Bašičević (Mangelos) of the avant-garde group Gorgona.(1) Kožarić often left his works without a signature or a date; one work spontaneously grew from another; works were arranged into cycles, and later into different ones in a never-ending process of permutation. His exploration of possibilities of the anti-sculptural and gestures of collectivity often went against and beyond the physical barriers of a single object and setting. What’s more, there were no boundaries between sculpture and the rest of the world. Sculpture as a medium was tested via the usage of conceptual proclamations, utopian concepts, textual works, drawings, paintings, performatives, encountered situations, urban interventions ...

The works created by Kožarić, whether object-based or of a conceptual nature, function as portals that look behind the existing into another dimension. This process is exemplified by his iconic sculpture “Unutarnje oči” (“Inner Eyes”, 1959—60), which expands into a negative, empty space. It consists of an enigmatic semicircular hollow object (of which he created several versions in different materials) that depicts the interior of a head (we assume the artist’s own) in which the two protruding forms signify the inward trajectory of a gaze. “Inner Eyes” is at once a self-portrait, a manifesto, and a portal. It traces a process in which the artistic gaze looks inward to penetrate the artist’s own head. Through these prosthetic inner eyes, his personal point of view is exposed to the viewers, from whose own point of view the inner eyes appear to stare back from the depths. Kožarić choose the photo of “Inner Eyes” for the cover of his edition of the “Gorgona” anti-magazine (no. 5) in 1961. This choice may have been a nod to the group’s having named itself “Gorgona” after the mythical creature whose divine visage petrified those who beheld it (also a kind of a “sculpturing” event). This choice reflects the Gorgonian collective search for more autonomous ways of producing and discussing art, which they held to be achievable only through a radical shift of perspective.

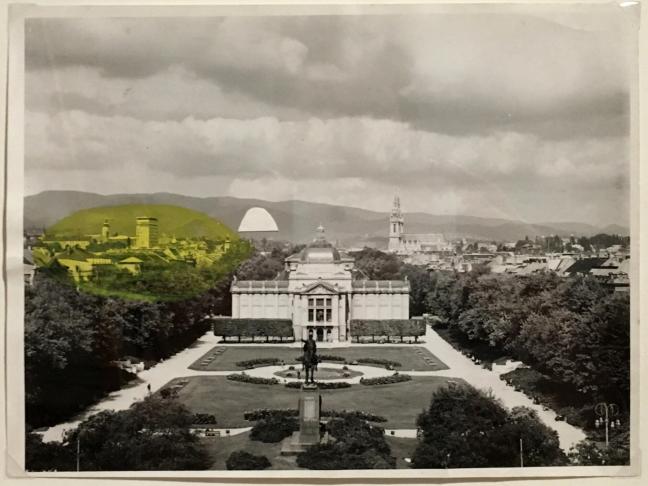

“Neobični projekt – Rezanje Sljemena” (“Uncommon Project – Cutting Sljeme”, 1960) takes sculpturing to another scale and dimension. Here, Kožarić proposed cutting into part of the Sljeme—a mountain peak popular among Zagreb-based hikers—and turning the landscape into sculptural material. Performative gestures and language were the medium that Gorgona group used for their projects. Kožarić’s “Kolektivno djelo” (“Collective Work”, 1963) proposes making plaster casts of the interiors of all the Gorgona members’ skulls—as well as of cars, of studios, and “mainly, then, of all the significant cavities in our city”. This work was initiated by an exercise suggested by another group member, art historian Radoslav Putar, who asked all members to propose their ideas for the group’s collective work. Kožarić’s proposal that resulted in “Collective Work” was the most remarkable, as a way of brilliantly expanding upon the idea of negative interior space originally worked with in his “Inner Eyes”.

Gorgona’s synergistic collective ethos, its transgressive ideas on the dissolution of art, catalyzed many of Kožarić’s projects that engaged with conceptualizing realms of negative and utopian sculptural space, which he viewed as being supplementary to external, concrete spaces. A text-based piece entitled “Proglas” (“Proclamation”, 1963–86)—which, in a spirit of collectivity, extends the invitation: “Sculptors of the world, let us make a cast of the Earth’s globe”—in many respects challenges our imaginations to conceive of their utopian potential as being feasible even as we postpone its realization until the future.

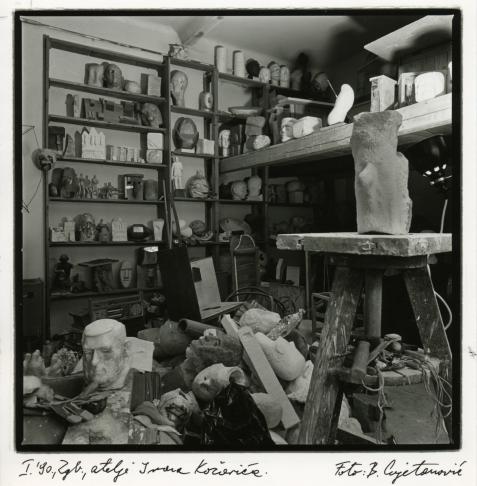

Regardless of these expansive energies, the quintessential space of Kožarić’s practice was a microcosm of his own studio, which was originally situated at 12 Medulićeva Street in Zagreb. It was a space that functioned as a junction, a point where all things come together to be invoked.

Being conceived of as an artistic “laboratory of revitalization”(2), his studio underwent numerous transformations. In 1971, he repainted almost everything in it—from sculptures from various periods to everyday objects—in a golden color, thereby equalizing his sculptural masterpieces with the non-art objects. Following this repainting in gold, 1993 saw the entire studio moved to the Zvonimir Gallery in Zagreb for his solo show, for the duration of which he also resided and worked there.(3) After that, the studio was presented in Kassel as part of 2002’s Documenta 11(4), an occasion for which its innate chaos was (ostensibly) structured. And finally, when Studio Kožarić entered the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, another (unexpected) transformation occurred: once all of the sculptures had been restored and wrapped neatly in acid-free paper, ready to be transported to the museum, Kožarić ecstatically decided to exhibit the sculptures while still wrapped—thereby rendering them “invisible”. It was one year later that the sculptures were finally unwrapped for all to see.

***

Another Gorgon, Dimitrije Bašičević (known from 1959 as Mangelos), based his “shid-manifesto” (1977) on “bio-psychological theory”, according to which the cells in a human body are exchanged in their entirety every seven years—meaning that at the conclusion of any such period, one is an entirely “new” person. Mangelos hence made note of “two Rimbauds, two Karl Marxes, three Van Goghs, several Picassos and nine-and-a-half Mangeloses”(5). To paraphrase him in an attempt to guess just how many Kožarićs exist, “a one and incommensurable” would seem a viable answer.

Kožarić’s oeuvre also exhibits a strong sense of humor—for in its use of unexpected and often surreal juxtapositions and dislocations, it also enables shifts in perspective on the part of the spectator. And at the present moment, with the horizon of old paradigms vanishing, we can view Kožarić’s oeuvre as an invitation to partake in the creation of future collective imaginaries. Employing the perspective of Kožarić’s art, this can be established by way of intuitive playfulness as well as via fearless de-hierarchization whose sphere of application includes the personal level. This is what makes his art so alive and so truly groundbreaking.

Ana Dević

(1) In addition to Kožarić, Gorgona included the painters Josip Vaništa, Marijan Jevšovar, Julije Knifer, and Đuro Seder; the architect Miljenko Horvat; the art historians Radoslav Putar, Matko Meštrović; and the art historian, curator and artist Dimitrije Bašicević (Mangelos). The group was active in Zagreb from 1959 to 1966.

(2) See Evelina Turković, “My Studio is a Laboratory for Vivification,” in “The Kožarić Studio”, Meta, Zagreb, 2002, p.80.

(3) This exhibition was initiated and curated by Antun Maračić.

(4) Kožarić was invited by Okwui Enwezor, artistic director of Documenta 11.

(5) See Branka Stipančić, “Mangelos from 1 to 9 ½, No-art”, Museu de Arte Contemporanea de Serrvales, Porto, 2003, p. 13.

The author would like to thank Radmila Iva Janković, curator of the Studio Kožarić at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb for collegially sharing her knowledge; Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, Boris Cvjetanović, Tomislav Pernar and his family, Dorotea Jendrić, Mio Vesović, and Goran Vranić.

Ana Dević is a curator and educator living in Zagreb. She is a member of curatorial collective What, How and for Whom/WHW.

November 2020