Maria Bartuszová at Tate Modern

/4

In recent years Tate Modern has been taking notable steps to give space, recognition, and visibility to female artists. Some of this much-needed and long-overdue attention has also been afforded to artists from Central Eastern Europe, hitherto largely eclipsed by their male counterparts, with few opportunities and little recognition enjoyed during their lifetimes, in some cases receiving international acclaim only posthumously.¹ This is indeed the case with the Slovak artist Maria Bartuszová (1936–1996) whose survey exhibition at Tate Modern follows a slew of recent posthumous solo exhibitions in her native Slovakia, Poland, an inclusion of her work in Documenta 12 and most recently in the 2022 Venice Biennale’s exhibition ‘The Milk of Dreams.’ Hot on the heels of these shows, Bartuszová’s 2022/23 survey at Tate Modern has been given an extended slot, lasting almost a year, providing audiences with a chance for repeat visits, and allowing for contextual research and for scholarly discourse to develop around the work.

This comprehensive exhibition includes over eighty works spanning thirty years of the Prague-born Slovak artist’s career, starting with early pieces from the 1960s and reaching into the late 1980s. The six-gallery exhibition is curated by Juliet Bingham, Tate’s Curator of International Art who has for some time been researching and exhibiting art of Central Eastern Europe and making significant inroads into improving the international visibility for artists from the region. Although modestly sized—but in fact just right for a perfectly balanced survey show— Bartuszová’s exhibition is a thorough, delicate, and sensitive exploration of her oeuvre, immersing the viewer in the artist’s methodical engagement with form and material, drawing out relations between art and life and making evident the artist’s interest in spirituality and flows of nature.

Bartuszová’s main material is plaster and it is plaster-casting that forms the basis her varied sculptural experiments, in some works combined with other materials. The exhibition is testament to Bartuszová’s development of new techniques and approaches, gradually building up a complex sculptural vocabulary pivoting around the endless possibilities of one material. Bartuszová’s explorations make evident the artist’s interest in the synchronicity with nature and its forms and materials, with the works in many cases appearing to be organic and not human made, at first glance easily mistaken for broken egg-shells, snow or peeling bark. Dozens of delicate white plaster sculptures of varying sizes dominate the space, some shown in clusters of vitrines, others floating weightlessly, suspended with string. Larger pieces hang on walls, interspersed with documentary photographs of Bartuszová’s outdoor sculptures, commissioned pieces and installations. The tactile and gentle works on display call for a slowing down, requiring stillness in what is almost monochrome space, providing a respite from distractions of media, moving images and constant sound alerts of our technologically driven lives.

The galleries are organized thematically, tracing a journey through Bartuszová’s methods and processes, immersing the viewer in the depths of her experimentation, gradually developing her process to include newly devised casting-techniques. Bartuszová’s early plaster works used simple everyday materials as molds, for instance balloons or condoms, submerging them in water, using gravity, blowing air into them, to crate organic, natural air pressure. She gradually perfected and developed complex techniques enabling larger works using weather balloons, such as ‘gravistimulated shaping’ involving the gravitational pull as a way of forming poured plaster, or ‘pneumatic casting,’ a technique of blowing air into balloons and pouring plaster over them.

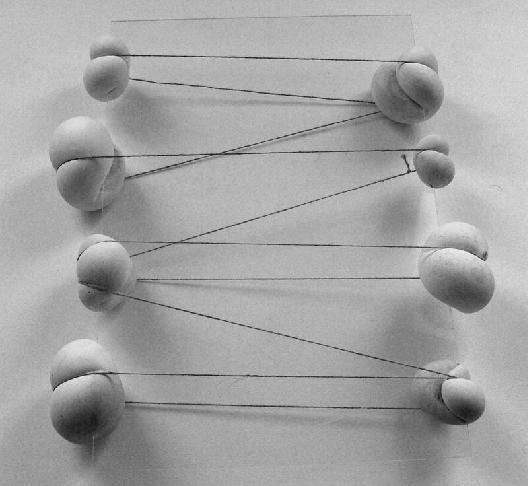

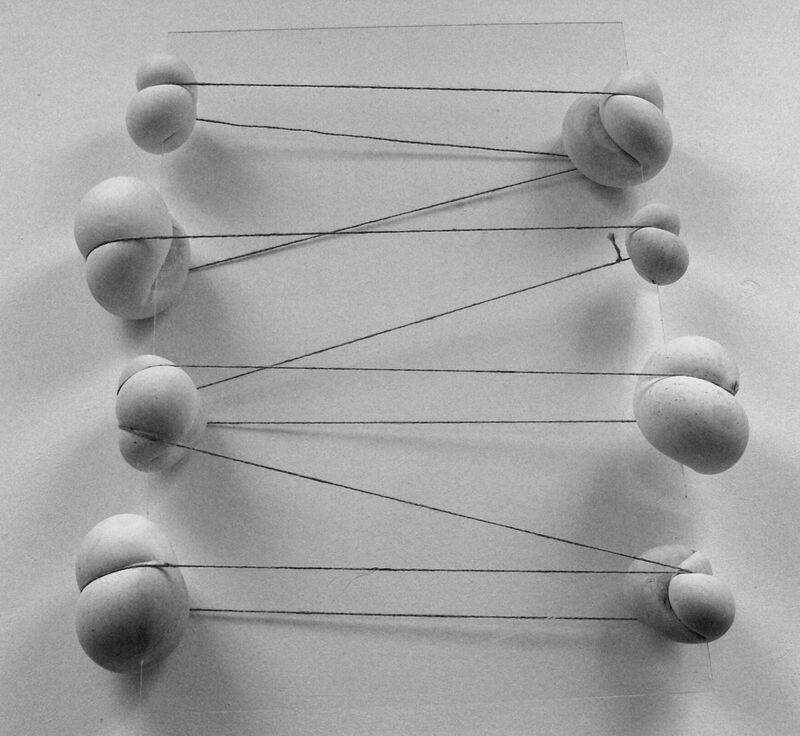

One of Bartuszová’s key interests lay in juxtaposing different materials and creating contrasts between the soft curves of the white plaster and hard, angular shapes of wood, the sharpness of rope, roughness of untreated rocks, the rigidity of various types of metal. For Bartuszová, the tension created between materials—flowing plaster bound with rope or ‘sandwiched’ between heavy rocks or wood, speaks of constraints on life a suffocating force limiting possibilities of living things.

There is in fact a certain frustration in seeing these objects with their haptic quality behind glass, ‘arrested’ in vitrines, or distantly positioned on plinths as they seductively fuel the viewers’ desire to reach out and touch them, but nevertheless remain out of reach due to their fragile nature. Indeed, some of the most moving and beautiful moments in the exhibition document these works ‘in action’, being handled by children in a workshop. Weaving Bartuszová’s life events into the display using previously unseen archive materials, the exhibition includes a series of photographs from 1976 which document workshops in a school in which children with visual impairments were invited to use Bartuszová’s sculptures. The enjoyment and fun are palpable in these photographs, showing groups of children laughing and playing as they handle the shapes, textures and explore the varying forms and sizes of sculptures, examining the works and interacting with each other. In these images the sculptures seem to have fulfilled their purpose, in that the haptic element is finally ‘put to work’ as the youngsters discover their texture, form, material and weight.²

Born in Prague, Maria Bartuszová became involved in the art scene in 1960s, at a time when conceptualism was taking hold of the Czechoslovakian alternative art practices, inspiring young artists of Bartuszová’s generation to reject the demands of socialist realism and break away from academic conventions. The Prague Spring in 1968, despite being brutally quashed by the Soviet Union, led to a loosening up of media, freeing up of public speech and improved international communication with artistic circles across Europe and the USA. Although travel was limited for artists, a more fluid exchange of ideas had an effect on Bartuszová‘s generation, providing opportunities for personal expression and a move away from prescribed artistic norms. Bartuszová’s influences were eclectic, and she looked to Japanese raku ceramic techniques on the one hand and Rodin’s sculpture on the other. Deeply moved by 20th century sculpture, Bartuszová found inspiration in particular aspects of works of artists as diverse as Constantin Brancusi, Lucio Fontana, Joan Miro and De Chirico, while her closest working relationship that nurtured and supported her practice was with her husband, the sculptor Juraj Bartusz.³ Raising a young family, Bartuszová moved after her studies to the slightly secluded town of Kosice. Although removed from the more dynamic art scene in Prague, Bartuszová was a member of the artists’ union which enabled her to draw an artists’ salary and benefit from numerous state commissions for outdoor public works, while in parallel dedicating herself to her more private, quiet methodical explorations of material, form and texture as seen in this exhibition. Deeply immersed in spiritual practices and cycles in nature, she sought to connect her sculpture to emotion, often drawing on play, meditation and therapy as well as engaging in what can be called a collaboration with natural processes, seasonal changes, elements such as water, air, and gravity. For Bartuszová the passing of time became a central element in her process of plaster-casting, linking with an exploration of the spiritual dimension of life.

Maria Bartuszová’s subtle and delicate practice draws the visitor into her world demonstrating what it means to commit to a medium and process, to devote a career to methodically pursuing an investigation, to learn through process and allow a practice to lead. Living in an accelerating world, with an increasing pace of life and ever-growing pressure on both humans and the environment, Bartusozva’s work is a reminder that another way is possible, one that values slowness, process, and deceleration, enabling us to breathe together a little easier.

Dr Lina Džuverović is a curator and academic based at Birkbeck, University of London

1

Other recent exhibitions of artists from the region at Tate Modern have included Dóra Maurer (2019 -21) and the current major exhibition of Magdalena Abakanowicz which coincides with Maria Bartuszová’s exhibition.

2

Bartuszová’s sculptures were used in 1976 and in 1983 in a series of workshops for blind and partially sighted children in Levoca, Czecholsovakia (now Slovakia), organised by art historian Gabriel Kladek who also photographed the workshops. For more information see the exhibition catalogue, pp. 32 – 41.

3

Bartuszová’s influences are listed in an excerpt from the artist’s diary, quoted in the exhibition catalogue curatorial text by Juliet Bingham. Maria Bartuszová, Eds Bingham, Juliet and Garlatyova, Gabriela, Tate Publishing, London, 2022, p. 13.

https://www.kontakt-collection.org/people/17/maria-bartuszova/objects

April 2023

This comprehensive exhibition includes over eighty works spanning thirty years of the Prague-born Slovak artist’s career, starting with early pieces from the 1960s and reaching into the late 1980s. The six-gallery exhibition is curated by Juliet Bingham, Tate’s Curator of International Art who has for some time been researching and exhibiting art of Central Eastern Europe and making significant inroads into improving the international visibility for artists from the region. Although modestly sized—but in fact just right for a perfectly balanced survey show— Bartuszová’s exhibition is a thorough, delicate, and sensitive exploration of her oeuvre, immersing the viewer in the artist’s methodical engagement with form and material, drawing out relations between art and life and making evident the artist’s interest in spirituality and flows of nature.

Bartuszová’s main material is plaster and it is plaster-casting that forms the basis her varied sculptural experiments, in some works combined with other materials. The exhibition is testament to Bartuszová’s development of new techniques and approaches, gradually building up a complex sculptural vocabulary pivoting around the endless possibilities of one material. Bartuszová’s explorations make evident the artist’s interest in the synchronicity with nature and its forms and materials, with the works in many cases appearing to be organic and not human made, at first glance easily mistaken for broken egg-shells, snow or peeling bark. Dozens of delicate white plaster sculptures of varying sizes dominate the space, some shown in clusters of vitrines, others floating weightlessly, suspended with string. Larger pieces hang on walls, interspersed with documentary photographs of Bartuszová’s outdoor sculptures, commissioned pieces and installations. The tactile and gentle works on display call for a slowing down, requiring stillness in what is almost monochrome space, providing a respite from distractions of media, moving images and constant sound alerts of our technologically driven lives.

The galleries are organized thematically, tracing a journey through Bartuszová’s methods and processes, immersing the viewer in the depths of her experimentation, gradually developing her process to include newly devised casting-techniques. Bartuszová’s early plaster works used simple everyday materials as molds, for instance balloons or condoms, submerging them in water, using gravity, blowing air into them, to crate organic, natural air pressure. She gradually perfected and developed complex techniques enabling larger works using weather balloons, such as ‘gravistimulated shaping’ involving the gravitational pull as a way of forming poured plaster, or ‘pneumatic casting,’ a technique of blowing air into balloons and pouring plaster over them.

One of Bartuszová’s key interests lay in juxtaposing different materials and creating contrasts between the soft curves of the white plaster and hard, angular shapes of wood, the sharpness of rope, roughness of untreated rocks, the rigidity of various types of metal. For Bartuszová, the tension created between materials—flowing plaster bound with rope or ‘sandwiched’ between heavy rocks or wood, speaks of constraints on life a suffocating force limiting possibilities of living things.

There is in fact a certain frustration in seeing these objects with their haptic quality behind glass, ‘arrested’ in vitrines, or distantly positioned on plinths as they seductively fuel the viewers’ desire to reach out and touch them, but nevertheless remain out of reach due to their fragile nature. Indeed, some of the most moving and beautiful moments in the exhibition document these works ‘in action’, being handled by children in a workshop. Weaving Bartuszová’s life events into the display using previously unseen archive materials, the exhibition includes a series of photographs from 1976 which document workshops in a school in which children with visual impairments were invited to use Bartuszová’s sculptures. The enjoyment and fun are palpable in these photographs, showing groups of children laughing and playing as they handle the shapes, textures and explore the varying forms and sizes of sculptures, examining the works and interacting with each other. In these images the sculptures seem to have fulfilled their purpose, in that the haptic element is finally ‘put to work’ as the youngsters discover their texture, form, material and weight.²

Born in Prague, Maria Bartuszová became involved in the art scene in 1960s, at a time when conceptualism was taking hold of the Czechoslovakian alternative art practices, inspiring young artists of Bartuszová’s generation to reject the demands of socialist realism and break away from academic conventions. The Prague Spring in 1968, despite being brutally quashed by the Soviet Union, led to a loosening up of media, freeing up of public speech and improved international communication with artistic circles across Europe and the USA. Although travel was limited for artists, a more fluid exchange of ideas had an effect on Bartuszová‘s generation, providing opportunities for personal expression and a move away from prescribed artistic norms. Bartuszová’s influences were eclectic, and she looked to Japanese raku ceramic techniques on the one hand and Rodin’s sculpture on the other. Deeply moved by 20th century sculpture, Bartuszová found inspiration in particular aspects of works of artists as diverse as Constantin Brancusi, Lucio Fontana, Joan Miro and De Chirico, while her closest working relationship that nurtured and supported her practice was with her husband, the sculptor Juraj Bartusz.³ Raising a young family, Bartuszová moved after her studies to the slightly secluded town of Kosice. Although removed from the more dynamic art scene in Prague, Bartuszová was a member of the artists’ union which enabled her to draw an artists’ salary and benefit from numerous state commissions for outdoor public works, while in parallel dedicating herself to her more private, quiet methodical explorations of material, form and texture as seen in this exhibition. Deeply immersed in spiritual practices and cycles in nature, she sought to connect her sculpture to emotion, often drawing on play, meditation and therapy as well as engaging in what can be called a collaboration with natural processes, seasonal changes, elements such as water, air, and gravity. For Bartuszová the passing of time became a central element in her process of plaster-casting, linking with an exploration of the spiritual dimension of life.

Maria Bartuszová’s subtle and delicate practice draws the visitor into her world demonstrating what it means to commit to a medium and process, to devote a career to methodically pursuing an investigation, to learn through process and allow a practice to lead. Living in an accelerating world, with an increasing pace of life and ever-growing pressure on both humans and the environment, Bartusozva’s work is a reminder that another way is possible, one that values slowness, process, and deceleration, enabling us to breathe together a little easier.

Dr Lina Džuverović is a curator and academic based at Birkbeck, University of London

1

Other recent exhibitions of artists from the region at Tate Modern have included Dóra Maurer (2019 -21) and the current major exhibition of Magdalena Abakanowicz which coincides with Maria Bartuszová’s exhibition.

2

Bartuszová’s sculptures were used in 1976 and in 1983 in a series of workshops for blind and partially sighted children in Levoca, Czecholsovakia (now Slovakia), organised by art historian Gabriel Kladek who also photographed the workshops. For more information see the exhibition catalogue, pp. 32 – 41.

3

Bartuszová’s influences are listed in an excerpt from the artist’s diary, quoted in the exhibition catalogue curatorial text by Juliet Bingham. Maria Bartuszová, Eds Bingham, Juliet and Garlatyova, Gabriela, Tate Publishing, London, 2022, p. 13.

https://www.kontakt-collection.org/people/17/maria-bartuszova/objects

April 2023