Raša Todosijević1945–2024

/2

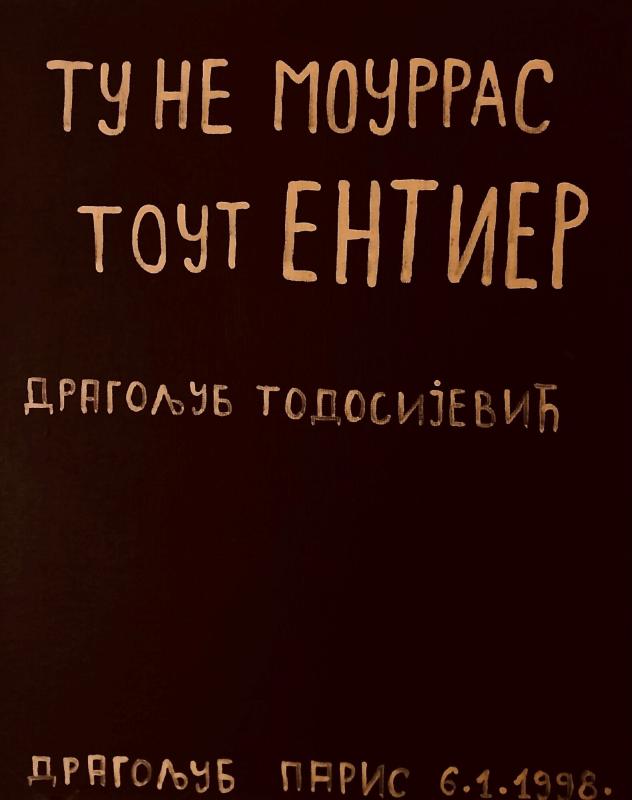

It was in one of those works on paper, cardboard, or other surfaces that he habitually executed over the decades that Raša Todosijević scribbled in his recognizable handwriting: Ту не моуррас тоут ентиер. This is a Cyrillic transliteration of the words Tu ne mourras tout entier (You will not completely die), jotted down by Francis Picabia atop his portrait representing Guillaume Apollinaire as a machine (1918). The sentence acts as a header for the epitaph that Picabia placed within this diagram of a machine-like tombstone dedicated to his deceased friend: “Guillaume Apollinaire – irritable poète.” Picabia was referring to “the irritable race of poets”, borrowing a line from the “Epistles” of Horace. Though Todosijević did not include this additional reference in his work, its implicit presence offers us a pertinent formulation via which to describe Todosijević’s uneasy relationship with the Serbian and Yugoslav artistic and cultural mainstream of the past fifty years. The performative instruments of his work were excitation, provocation, and annoyance—achieved not through negation but by studying, theorizing, and ultimately critically reversing the substance and meaning of the modernist autonomy of art. ln his text “Art and Revolution” (1975), an antagonistic and dissensual commitment to art is put forth with the claim that “only in ethical, political, and social clashes does art sharpen and underline its meaning.”

One could mention numerous examples of the “irritability” of Todosijević’s poetry. In his early performance “Water Drinking” (1974), the setting included a small aquarium containing a common fish: a carp. The artist removed the carp and placed it in front of his audience, high and dry. He then drank water from the aquarium as the fish suffocated, attempting to synchronize the rhythm of his gulps with the rhythm of the breaths taken by the dying fish. After a while, he was full and started vomiting on a table. During one of this work’s realizations, a person who was deeply angered by this irritating procedure proceeded to interact with the performance—returning the fish back to the aquarium. In this case, the making of art was bluntly understood as a counter-natural act: the attempt at harmony between nature and art as a violent affair.

In works including “Decision as Art” (1973), “Vive la France,” and “Vive la Tyrannie” (1979), as well, and in his “Schlafflage” installations from the early 1980s, Todosijević poked holes in the corrupted myth that there is something inherently humane and humanistic in the modernist institution of art. While a student at Belgrade’s Academy of Arts during the late 1960s, Todosijević was confronted with the paradox that while the art of “moderate modernism” relied on the humanist discourse surrounding the freedom of men and the freedom of creation, its protagonists gave themselves over to the accumulation of power and social prestige—controlling a system that fostered mediocracy. To him, the local pantheon of artists stood in disproportion to the world of art that he was investigating. And to Todosijević and others of his generation, it was figures such as Duchamp, Malevich, Schwitters, Reinhardt, Morris, and Beuys who upheld the only relevancy of the word art, whilst their professors at the Academy of Arts showed no desire to share anything in common with these epigones of the École de Paris.

An aspiration to his own aleatoric history of art was exercised in another early performance, “Art and Memory” (1975), a four-hour recitation of coincidentally recalled artists’ names done with his face covered by a decorative bandana such as one imagines being worn by thieves or terrorists. And in his best-known work, “Was ist Kunst?” (1976–78), he aggressively posed this impossible question—“What is art?”—with obdurate repetitiveness. As Dejan Sretenović has noticed, the method of these performances is akin to the notion behind Antonin Artaud’s “theatre of cruelty”—in which a work of art does not save its recipients from their tragic condition but rather confronts them therewith. Or, in Todosijević’s own words: “My performances seek to irritate a negative side of man in order to make him aware of it; your bitterness after the performance is that negative side of you.” Todosijević’s work is inherently connected with threads of the anti-humanist philosophies of Althusser and Lacan, although these were never direct influences. Much like Althusser, he was aware that “it is impossible to know anything about men except on the absolute precondition that the philosophical (theoretical) myth of man is reduced to ashes.” And much like in Lacanian psychoanalysis, the goal of his performances (sessions) was to reorient viewers’ (patients’) relationship with the Real so that they could dissolve their symptoms and change or interrupt how they desired.

When the Yugoslav federation and its entire enterprise of humanist socialism was reduced to ashes, to be replaced by petty bourgeois parochialism and nationalist intoxication, Todosijević’s mission became to irritate the dominant ideological desires by overidentifying with them. In the early 1990s, he set out to antagonize the entire cultural and ideological edifice in Serbia and its mythical constructions in a long-running series of works entitled “Gott Liebt die Serben,” which—like “Was ist Kunst?”—employed German as a language that has linked high culture with organized terror. The artistic language of this project was only seemingly less performative than that of the 1970s work. This language materialized in large installations featuring drawings, watercolors, readymade objects, labels, and texts of ferocity and bitter irony that cultivated a distinct form of (self-)insult. In these works, Raša occasionally acted as “an artistic pig” or “a Serbo-Bolshevik and a Thief” who pseudo-authoritatively claimed that “God Exists” or boasted of being an “Über-Srbin”. A hymn in his honor, composed by Mipi Savić in 1999, was presented. In some works, the entire state of Serbia expressed its “gratitude” for his art. And on the occasion of his 65th birthday, “all Serbian artists, critics, museums and galleries, with their own miserable, relapsed, and culturally worthless attempts” wished him a happy birthday on the behalf of “The Patriotic Bootlicker Society.”

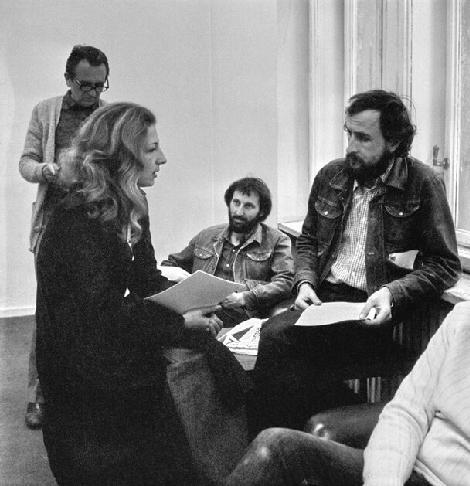

On a personal note, I met Raša and his lifelong partner Marinela Koželj for the first time during the early 1990s, when my generation of artists and curators was becoming deeply interested in the artists of their generation. We went on to collaborate numerous times—most recently on the series of low-fi exhibitions entitled “Beaux-arts serbes” (2018–21), in which he showed his latest series of works that weirdly invoked the spiritualism of early 20th-century coloristic and geometric abstraction. However, it was only recently that I realized from reading his essay on Robert Smithson, published in the first issue of the magazine Moment (1984), how my interest in contemporary art and theory had been prompted by Smithson’s dialectics of site and non-site that Todosijević so thoroughly discussed there. And in concluding this attempt at an obituary, I would also like to say that Raša needs to be remembered and studied not only as a groundbreaking artist but also as a non-institutional art educator and an author of short stories in the form of condensed vignettes of direct narration situated somewhere between ironic philosophizing and folktales with better- or less-known characters. These he regularly wrote but only occasionally published, and they still await comprehensive reflection.

Dragoljub Raša Todosijević passed away in Belgrade on 3 December 2024.

Branislav Dimitrijević

Branislav Dimitrijević is professor of history and theory of art at the School for Art and Design in Belgrade. He teaches and writes internationally on the art, cinema and politics of socialist Yugoslavia; on avant-garde art, contemporary art and exhibition histories.

https://www.kontakt-collection.org/people/55/rasa-todosijevic/objects

February 2025

One could mention numerous examples of the “irritability” of Todosijević’s poetry. In his early performance “Water Drinking” (1974), the setting included a small aquarium containing a common fish: a carp. The artist removed the carp and placed it in front of his audience, high and dry. He then drank water from the aquarium as the fish suffocated, attempting to synchronize the rhythm of his gulps with the rhythm of the breaths taken by the dying fish. After a while, he was full and started vomiting on a table. During one of this work’s realizations, a person who was deeply angered by this irritating procedure proceeded to interact with the performance—returning the fish back to the aquarium. In this case, the making of art was bluntly understood as a counter-natural act: the attempt at harmony between nature and art as a violent affair.

In works including “Decision as Art” (1973), “Vive la France,” and “Vive la Tyrannie” (1979), as well, and in his “Schlafflage” installations from the early 1980s, Todosijević poked holes in the corrupted myth that there is something inherently humane and humanistic in the modernist institution of art. While a student at Belgrade’s Academy of Arts during the late 1960s, Todosijević was confronted with the paradox that while the art of “moderate modernism” relied on the humanist discourse surrounding the freedom of men and the freedom of creation, its protagonists gave themselves over to the accumulation of power and social prestige—controlling a system that fostered mediocracy. To him, the local pantheon of artists stood in disproportion to the world of art that he was investigating. And to Todosijević and others of his generation, it was figures such as Duchamp, Malevich, Schwitters, Reinhardt, Morris, and Beuys who upheld the only relevancy of the word art, whilst their professors at the Academy of Arts showed no desire to share anything in common with these epigones of the École de Paris.

An aspiration to his own aleatoric history of art was exercised in another early performance, “Art and Memory” (1975), a four-hour recitation of coincidentally recalled artists’ names done with his face covered by a decorative bandana such as one imagines being worn by thieves or terrorists. And in his best-known work, “Was ist Kunst?” (1976–78), he aggressively posed this impossible question—“What is art?”—with obdurate repetitiveness. As Dejan Sretenović has noticed, the method of these performances is akin to the notion behind Antonin Artaud’s “theatre of cruelty”—in which a work of art does not save its recipients from their tragic condition but rather confronts them therewith. Or, in Todosijević’s own words: “My performances seek to irritate a negative side of man in order to make him aware of it; your bitterness after the performance is that negative side of you.” Todosijević’s work is inherently connected with threads of the anti-humanist philosophies of Althusser and Lacan, although these were never direct influences. Much like Althusser, he was aware that “it is impossible to know anything about men except on the absolute precondition that the philosophical (theoretical) myth of man is reduced to ashes.” And much like in Lacanian psychoanalysis, the goal of his performances (sessions) was to reorient viewers’ (patients’) relationship with the Real so that they could dissolve their symptoms and change or interrupt how they desired.

When the Yugoslav federation and its entire enterprise of humanist socialism was reduced to ashes, to be replaced by petty bourgeois parochialism and nationalist intoxication, Todosijević’s mission became to irritate the dominant ideological desires by overidentifying with them. In the early 1990s, he set out to antagonize the entire cultural and ideological edifice in Serbia and its mythical constructions in a long-running series of works entitled “Gott Liebt die Serben,” which—like “Was ist Kunst?”—employed German as a language that has linked high culture with organized terror. The artistic language of this project was only seemingly less performative than that of the 1970s work. This language materialized in large installations featuring drawings, watercolors, readymade objects, labels, and texts of ferocity and bitter irony that cultivated a distinct form of (self-)insult. In these works, Raša occasionally acted as “an artistic pig” or “a Serbo-Bolshevik and a Thief” who pseudo-authoritatively claimed that “God Exists” or boasted of being an “Über-Srbin”. A hymn in his honor, composed by Mipi Savić in 1999, was presented. In some works, the entire state of Serbia expressed its “gratitude” for his art. And on the occasion of his 65th birthday, “all Serbian artists, critics, museums and galleries, with their own miserable, relapsed, and culturally worthless attempts” wished him a happy birthday on the behalf of “The Patriotic Bootlicker Society.”

On a personal note, I met Raša and his lifelong partner Marinela Koželj for the first time during the early 1990s, when my generation of artists and curators was becoming deeply interested in the artists of their generation. We went on to collaborate numerous times—most recently on the series of low-fi exhibitions entitled “Beaux-arts serbes” (2018–21), in which he showed his latest series of works that weirdly invoked the spiritualism of early 20th-century coloristic and geometric abstraction. However, it was only recently that I realized from reading his essay on Robert Smithson, published in the first issue of the magazine Moment (1984), how my interest in contemporary art and theory had been prompted by Smithson’s dialectics of site and non-site that Todosijević so thoroughly discussed there. And in concluding this attempt at an obituary, I would also like to say that Raša needs to be remembered and studied not only as a groundbreaking artist but also as a non-institutional art educator and an author of short stories in the form of condensed vignettes of direct narration situated somewhere between ironic philosophizing and folktales with better- or less-known characters. These he regularly wrote but only occasionally published, and they still await comprehensive reflection.

Dragoljub Raša Todosijević passed away in Belgrade on 3 December 2024.

Branislav Dimitrijević

Branislav Dimitrijević is professor of history and theory of art at the School for Art and Design in Belgrade. He teaches and writes internationally on the art, cinema and politics of socialist Yugoslavia; on avant-garde art, contemporary art and exhibition histories.

https://www.kontakt-collection.org/people/55/rasa-todosijevic/objects

February 2025