The Cynics Republic – 2500 Years of Performance

/16

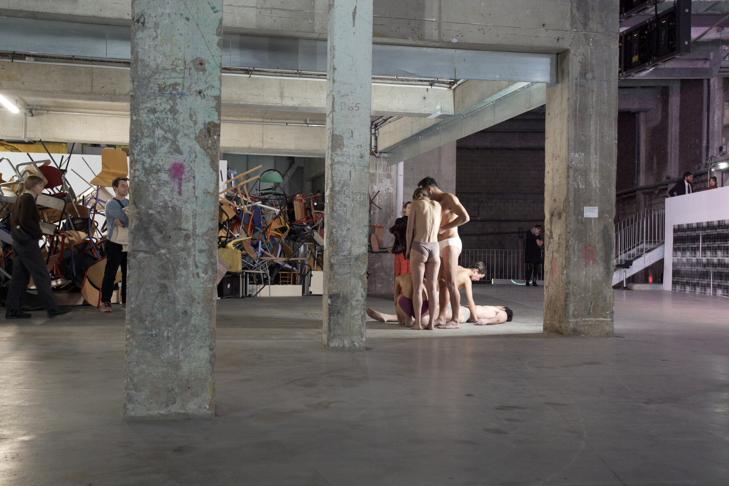

“The Cynics Republic,” which unfolded over a period of three weeks in accordance with an exhibition score created by Pierre Bal-Blanc, conveyed a counter-narrative to the history of performance. Staged at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, this exhibition drew mainly on dematerialized works (scores, protocols, films, and sound pieces) from the collections of Cnap and Kontakt.

The term “Republic” in the exhibition’s title points to governance as a central theme. Bal-Blanc suggests that every important ancient philosopher put forth his own “Republic” as a constitution of sorts, a theoretical proposition providing instructions on how to govern. In the context of this exhibition, governance denotes the organization to which the relationships between artists, visitors/spectators, performers, people working within the institution, and the building itself are subject. “The Cynics Republic” pursues a temporary yet radical proposition pertaining to such organization’s transformation. The compositional and instructional nature of Bal-Blanc’s curatorial framing underlines how he relates to performativity, with “The Cynics Republic” proposing an embodied and transient experience—one that questions the singularity of each visitor’s encounter with the space, the objects’ materiality, and the performers’ bodies.

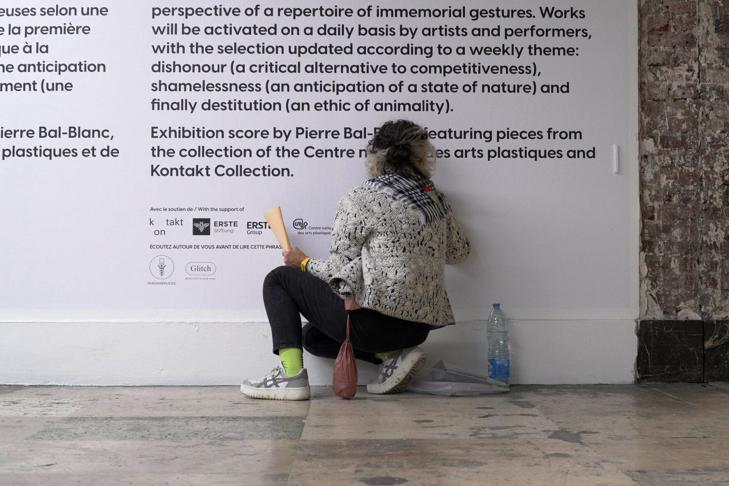

Bal-Blanc’s research concerning cynicism began while he was living and working in Athens in the context of Documenta 14. Having encountered this ancient philosophical tradition in the writings of Michel Foucault¹ and taken further inspiration from philosopher Suzanne Husson’s “La république de Diogène,”² Bal-Blanc stresses that cynicism has been profoundly impoverished by its modern and colloquial understanding. He notes that ancient cynicism manifested itself as a holistic philosophy, refusing to separate the mind, the body, and their non-human environment. He emphasizes how the Cynics privileged oral transmission as well as gestures, attitudes, and situations in the public realm as exemplified by the approximately 200 fragments³ that he collected over the course of his research. For the curator, these fragments afford access to a collectively shared resource that must be regarded as a protohistory of performance that traces its genealogy back to classical antiquity rather than to the early 20th century. The works borrowed from the collections of both Cnap and Kontakt merge into this transhistorical index of gestures, of “useful and accessible minor postures.” Engaging with the ethics of ancient cynicism, Bal-Blanc isolated notions of dishonor as “a critical alternative to competitiveness”, shamelessness as “an anticipation of a state of nature,” and destitution as “autarky, an ethics of animality.” These three ideas enabled the curator to engage with critical perspectives on our current social and political situation while also serving as a pivotal week-by-week framework for the exhibition’s organization.

The exhibition took place in spaces situated at the margins of the art center—bringing its visitors down to the lowest floor of the building, away from the institution’s buzzing multitude of other activities. It began with a drawing by Étienne Baudet after Nicolas Poussin⁴ that shows the cynic philosopher Diogenes addressing a young man who is drinking water from a stream with cupped hands. With this work, Bal-Blanc introduced a scene exemplary of Cynical values—featuring the simplicity of drinking with one’s hands—and directed our attention toward an institution in the picture’s background (the Villa Belvedere in Rome) in reference to the origins of the museum as an institution geared toward conserving objects and building a stable cultural identity. The works brought together in “The Cynics Republic” changed daily except for those that constituted a “continuum,” an ensemble of works such as Franz West’s “Auditorium” (1992) or Dominique Mathieu’s “Barricade” (2009), which were presented all the way through the exhibition. The underlying score allowed Bal-Blanc to play with various rhythms, textures, and dynamics. The exhibition’s compositional structure introduced fluidity and adaptation to the heterogeneity and instability inherent in the dematerialized and performative works assembled by Pierre Bal-Blanc in this setting.

Bal-Blanc’s choice of the Palais de Tokyo for this exhibition enabled him to collaborate closely with the venue’s technical team. Doing so facilitated crucial engagement with the material environment and made it possible for the exhibition to be continuously reconfigured. “The Cynics Republic” revealed equivalence as an essential feature of the history of performance, refuting the value of originality and singularity. The exhibition incorporated a broad spectrum of practices, affirming a common ground shared by practices in the respective fields of conceptual art, music, choreography, and performance. With “The Cynics Republic,” Pierre Bal-Blanc gave rise to a situation that amounted to an overwhelming proposition: though nobody save for Bal-Blanc himself was able experience it in its entirety, it made an attempt to convey performance practices’ vitality and fleeting nature. “The Cynics Republic” foregrounded how performance relates to repetition, rhythmic erraticism, slowness and duration, uncertainty and unpredictability. These characteristics radically contradict the values of efficacy and efficiency, which define performance in contemporary economic and social contexts. In a world of limited resources that is nonetheless ruled by competitiveness, exploitation, and privatization, “The Cynics Republic” lent visibility to artistic and curatorial strategies whose dematerialized and performative forms tell a different story, a counter-narrative based on shared resources, regeneration, and endless transformation.

Vanessa Desclaux is a writer and curator based in Bordeaux, France. She is a lecturer in art history and theory at the École Nationale Supérieure d'art & design in Dijon.

1

Michel Foucault addressed ancient cynicism in his final lectures at the Collège de France, given from February to March 1984. He died a few months later, in June 1984.

2

Suzanne Husson, La république de Diogène, Vrin, 2015

3

On the occasion of this exhibition, these fragments were published in a booklet that was distributed free of charge to visitors.

4

Étienne Baudet (b. ca. 1638, Vineuil, France, d. 1711), “Paysage avec Diogène” after Nicolas Poussin (1701), copperplate engraving. Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques, Paris

March 2025

The term “Republic” in the exhibition’s title points to governance as a central theme. Bal-Blanc suggests that every important ancient philosopher put forth his own “Republic” as a constitution of sorts, a theoretical proposition providing instructions on how to govern. In the context of this exhibition, governance denotes the organization to which the relationships between artists, visitors/spectators, performers, people working within the institution, and the building itself are subject. “The Cynics Republic” pursues a temporary yet radical proposition pertaining to such organization’s transformation. The compositional and instructional nature of Bal-Blanc’s curatorial framing underlines how he relates to performativity, with “The Cynics Republic” proposing an embodied and transient experience—one that questions the singularity of each visitor’s encounter with the space, the objects’ materiality, and the performers’ bodies.

Bal-Blanc’s research concerning cynicism began while he was living and working in Athens in the context of Documenta 14. Having encountered this ancient philosophical tradition in the writings of Michel Foucault¹ and taken further inspiration from philosopher Suzanne Husson’s “La république de Diogène,”² Bal-Blanc stresses that cynicism has been profoundly impoverished by its modern and colloquial understanding. He notes that ancient cynicism manifested itself as a holistic philosophy, refusing to separate the mind, the body, and their non-human environment. He emphasizes how the Cynics privileged oral transmission as well as gestures, attitudes, and situations in the public realm as exemplified by the approximately 200 fragments³ that he collected over the course of his research. For the curator, these fragments afford access to a collectively shared resource that must be regarded as a protohistory of performance that traces its genealogy back to classical antiquity rather than to the early 20th century. The works borrowed from the collections of both Cnap and Kontakt merge into this transhistorical index of gestures, of “useful and accessible minor postures.” Engaging with the ethics of ancient cynicism, Bal-Blanc isolated notions of dishonor as “a critical alternative to competitiveness”, shamelessness as “an anticipation of a state of nature,” and destitution as “autarky, an ethics of animality.” These three ideas enabled the curator to engage with critical perspectives on our current social and political situation while also serving as a pivotal week-by-week framework for the exhibition’s organization.

The exhibition took place in spaces situated at the margins of the art center—bringing its visitors down to the lowest floor of the building, away from the institution’s buzzing multitude of other activities. It began with a drawing by Étienne Baudet after Nicolas Poussin⁴ that shows the cynic philosopher Diogenes addressing a young man who is drinking water from a stream with cupped hands. With this work, Bal-Blanc introduced a scene exemplary of Cynical values—featuring the simplicity of drinking with one’s hands—and directed our attention toward an institution in the picture’s background (the Villa Belvedere in Rome) in reference to the origins of the museum as an institution geared toward conserving objects and building a stable cultural identity. The works brought together in “The Cynics Republic” changed daily except for those that constituted a “continuum,” an ensemble of works such as Franz West’s “Auditorium” (1992) or Dominique Mathieu’s “Barricade” (2009), which were presented all the way through the exhibition. The underlying score allowed Bal-Blanc to play with various rhythms, textures, and dynamics. The exhibition’s compositional structure introduced fluidity and adaptation to the heterogeneity and instability inherent in the dematerialized and performative works assembled by Pierre Bal-Blanc in this setting.

Bal-Blanc’s choice of the Palais de Tokyo for this exhibition enabled him to collaborate closely with the venue’s technical team. Doing so facilitated crucial engagement with the material environment and made it possible for the exhibition to be continuously reconfigured. “The Cynics Republic” revealed equivalence as an essential feature of the history of performance, refuting the value of originality and singularity. The exhibition incorporated a broad spectrum of practices, affirming a common ground shared by practices in the respective fields of conceptual art, music, choreography, and performance. With “The Cynics Republic,” Pierre Bal-Blanc gave rise to a situation that amounted to an overwhelming proposition: though nobody save for Bal-Blanc himself was able experience it in its entirety, it made an attempt to convey performance practices’ vitality and fleeting nature. “The Cynics Republic” foregrounded how performance relates to repetition, rhythmic erraticism, slowness and duration, uncertainty and unpredictability. These characteristics radically contradict the values of efficacy and efficiency, which define performance in contemporary economic and social contexts. In a world of limited resources that is nonetheless ruled by competitiveness, exploitation, and privatization, “The Cynics Republic” lent visibility to artistic and curatorial strategies whose dematerialized and performative forms tell a different story, a counter-narrative based on shared resources, regeneration, and endless transformation.

Vanessa Desclaux is a writer and curator based in Bordeaux, France. She is a lecturer in art history and theory at the École Nationale Supérieure d'art & design in Dijon.

1

Michel Foucault addressed ancient cynicism in his final lectures at the Collège de France, given from February to March 1984. He died a few months later, in June 1984.

2

Suzanne Husson, La république de Diogène, Vrin, 2015

3

On the occasion of this exhibition, these fragments were published in a booklet that was distributed free of charge to visitors.

4

Étienne Baudet (b. ca. 1638, Vineuil, France, d. 1711), “Paysage avec Diogène” after Nicolas Poussin (1701), copperplate engraving. Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques, Paris

March 2025