Rosa coeli

/7

- Rosa coeli

- 2003

- 35mm film transferred to video, b&w, sound

- 23min, 11sec

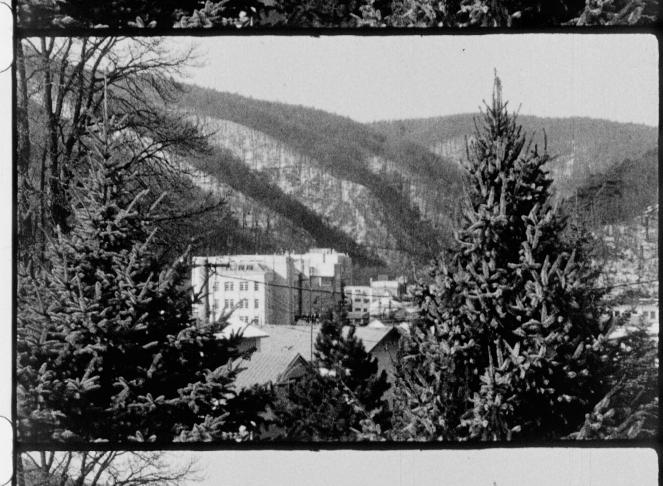

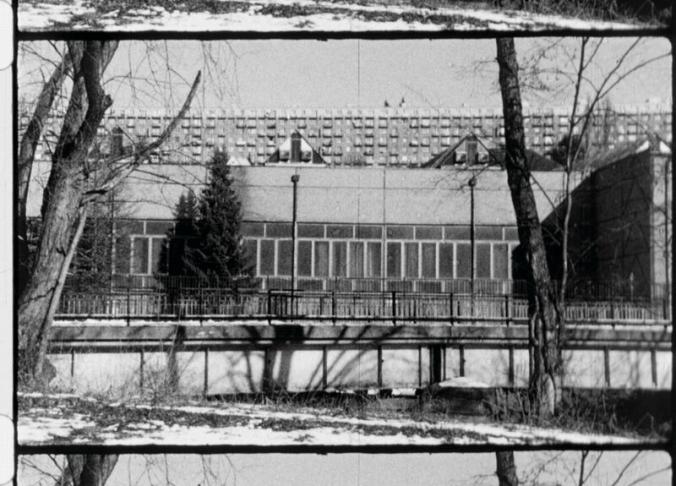

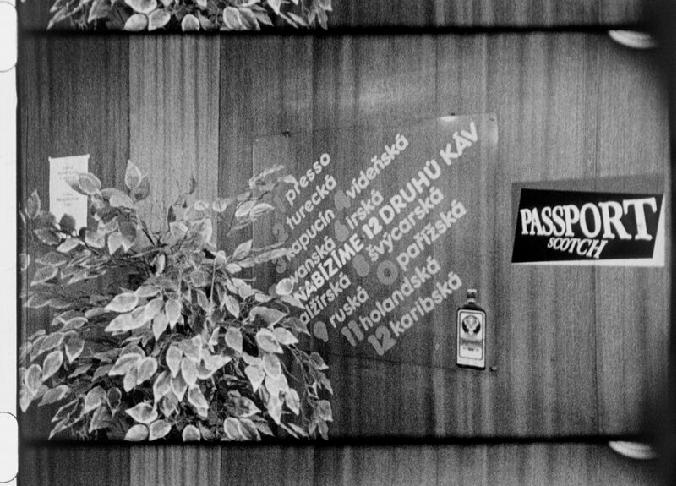

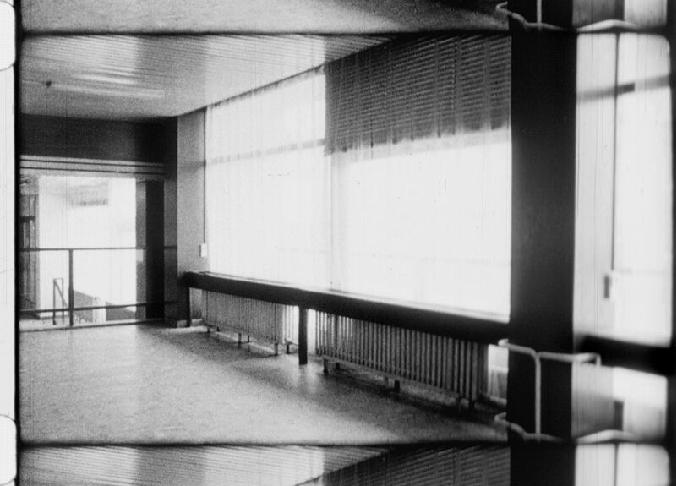

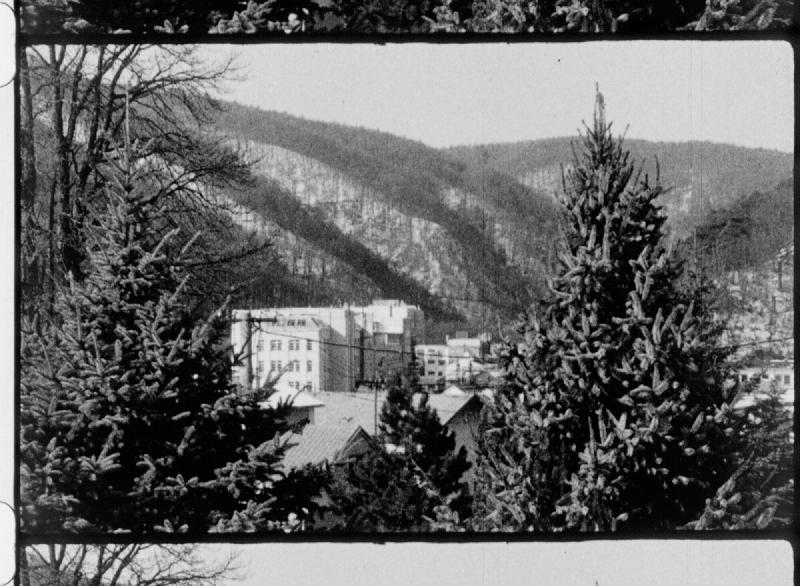

In “Rosa Coeli,” various movement motifs interlace to become conglomerates of action: one strand shows scenes from a train trip by one of the protagonists to a hotel in a mountain industrial village. This settlement is easily recognized as one with a “real socialist” past. This backdrop of a run-down Eastern European modernist hotel, devoid of any audience or media, in which the protagonist meets with two other men—physically handicapped, as is he—to silently sign a piece of paper at a ceremonially decorated table, embodies something of a second leading role in “Rosa Coeli”. In a rhythmic sequence of scenes, both the act of signing and the hotel’s design history begin to unfold: fragments of stereotypical movement patterns such as greetings, turning over a sheet of paper, and glimpses of details such as game machines, dreary houseplants before the chrome, glass and artificial stone of the hotel’s lobby, and hybrid-pop lighting elements from that era during which the building probably served as lodgings for state functionaries from the politburo or worker’s organizations. In tandem with the cuts between the two stories, the sound space also changes. Bruno Pellandinis’s stylized high-literature text on the return to a lost-in-time, Eastern European place from childhood shifts the viewer’s attention from the visual choppiness of the action or plot to the still life. The stills, which seem to have fallen out of the depths of time, burst apart the narrative frame of the text. With determined calm and unshakably well-rehearsed mechanical execution, Dabernig’s amateur actors play through this double-plot which results nothing other than its nearly uncanny presence. G.S.