Bad God

/4

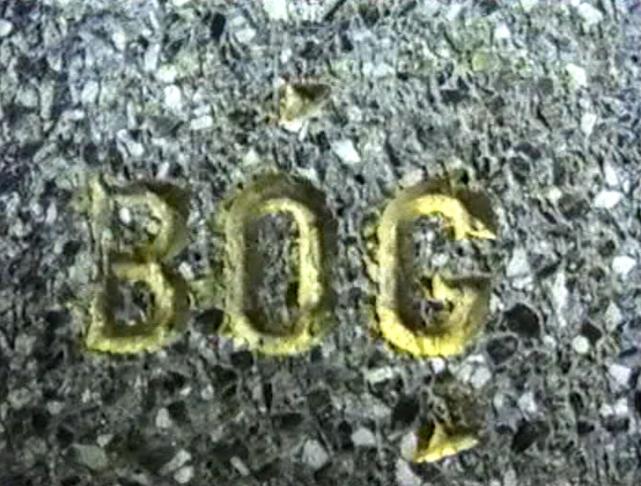

- Bad God

- Zly Bóg

- 1988

- video, color

- 3min, 22sec

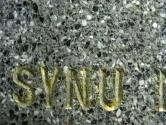

In “Kakos Daimon,” Libera superimposes ancient Greek and Hellenistic tradition onto Christian, Catholic traditions. The gravestone’s “golden” inscription appears here in narrative sequences similar to those in “Me Alus…” (1988), resembling Jenny Holzer’s “advertisement” poetry on electronic billboards. The naïve, passionate inscription written by the parents of the 21-year-old volunteer soldier is translated into Greek in subtitles. It becomes both hymn and epitaph of Pabianice, with “cheap” rhymes addressed to the beloved son in its poetic apostrophe, describing his devotion to “homeland and nation,” his enigmatic plans, his motivations, and his parent’s love for a son taken away by God and a “treacherous hand.” Interestingly, even the title is suggestive of Libera’s non-Catholic and perhaps even mocking reading of the situation, possibly referencing a gnostic god or a daemon. The Greek compound of “kakos” and “daimon,” “kakodaimon,” does not translate literally into “bad god.” A kakodaimon was an “evil spirit,” a type of daemon opposed to the good spirits such as the agathodaimon or eudaimon. For Socrates and Plato, daemons were our “comrades,” spirits situated between the gods and human beings, who assisted us during life and after death. But they also possessed and intoxicated people with the “spirit of motivation,” and were therefore categorized by the Greeks as “‘bad.” This aspect recalls Libera’s interest in the Heideggerian deterministic concept of “Dasein”, “being-towards-death,” existence as a project, and life motivated by fear of death. A year before, in 1987, Libera had made a collage in the style of Kultura Zrzuty, titled “Christian Death according to Heidegger” [“Chrzescijanska smierc wg Heideggera”], which depicted his mother and himself. B.P.